by Lila Powers

What Happened

Henry Kuhl’s son, Christian, wrote in his memoirs (written in 1911) that, “On the 31st day of May, 1861, there arose a cry. The Abolitionists are coming over from Ohio and elsewhere from the Nort h to invade Virginia (now West Virginia), overrunning our country, destroying property, compelling our men to enlist, taking horses, cattle, arms, ammunitions, and insulting mothers and wives where the men had fled or refugeed. This was too strong a proposition for freemen to sit still and cross arms in a

h to invade Virginia (now West Virginia), overrunning our country, destroying property, compelling our men to enlist, taking horses, cattle, arms, ammunitions, and insulting mothers and wives where the men had fled or refugeed. This was too strong a proposition for freemen to sit still and cross arms in a  chair and do nothing, or to take sides with. I, with many of my fellow citizens of Gilmer County, gathered all available arms and ammunitions, which in the main consisted of a squirrel rifle, a few rounds of ammunition, sometimes a dirk knife, a revolver, or old fashioned revolver then known by the name of Pepper boxes.”1 These citizens organized a company of infantry volunteers, which afterward became Company D of the 31st Regiment Virginia Volunteer Infantry.

chair and do nothing, or to take sides with. I, with many of my fellow citizens of Gilmer County, gathered all available arms and ammunitions, which in the main consisted of a squirrel rifle, a few rounds of ammunition, sometimes a dirk knife, a revolver, or old fashioned revolver then known by the name of Pepper boxes.”1 These citizens organized a company of infantry volunteers, which afterward became Company D of the 31st Regiment Virginia Volunteer Infantry.Left, Henry Kuhl and his first wife, Catherine Yeagle. Catherine died in 1854 at the age of 50. Henry and Catherine and several children came to America from the Rheinland.

Right: Henry's second wife, Elizabeth Skidmore.

Right, below: examples of pepper box revolvers

A couple of months later (on or about the first day of August, 1861), a boy around 15 or 16 years old dressed as a Union soldier came to Henry Kuhl’s home. Henry Kuhl, Conrad Kuhl, Hamilton Windon, and John Conrad were out working in

Henry’s field when Henry’s wife, Elizabeth, came out to tell the men that the boy had been at the house again. The boy had come to the house the previous day as well. Elizabeth said she had given the boy food, and he was leaving the farm. Two of the men went after him, and brought him back to the field where they confronted him. The details of what actually happened on that summer day in 1861 are unclear, but before the day had ended, the boy had been mortally wounded.

Henry’s field when Henry’s wife, Elizabeth, came out to tell the men that the boy had been at the house again. The boy had come to the house the previous day as well. Elizabeth said she had given the boy food, and he was leaving the farm. Two of the men went after him, and brought him back to the field where they confronted him. The details of what actually happened on that summer day in 1861 are unclear, but before the day had ended, the boy had been mortally wounded.Left, above and right:

These are recent photos of the former Kuhl farm where the event unfolded. They were provided by Marilyn (Cole) Posey. Identified are

1. where the house stood

2. where the boy was killed

3. the stone grave where the boy was found.

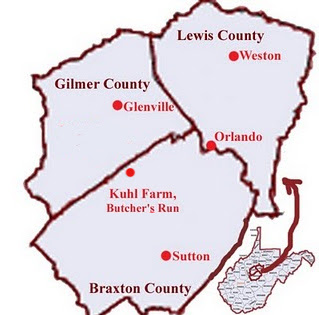

Left, below: a map of 3 central WV counties, Braxton, Gilmer and Lewis, illustrating the approximate location of the Kuhl farm.

During the same period in 1861, Companies B, C, and H of the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (O.V.I.) were in the Glenville area looking for “rebels”. Corporal Adams of Company C was shot and seriously wounded there by a “bushwhacker” on the 21st of July. “The whole regiment came out, but failed to discover the rebel after diligent search.”11 The fact that the boy arrived at Henry Kuhl’s farm around this time must have caused some concern, especially when the boy said he was looking for secessionists, good horses, and guns. Two of Henry’s sons were Confederate soldiers, so the me

n knew they could expect to be treated as the enemy if this i

n knew they could expect to be treated as the enemy if this information were to reach the Union soldiers. A Federal Confiscation Act was about to be approved that would authorize the military to take property from Confederate sympathizers.15 These farmers were not secessionists or rebels, but Union soldiers would most likely not find that believable. Recent news of the brutal killing of a local citizen, Thomas Stout, by a Union soldier who had mistaken him for a rebel12, strengthened the farmers’ resolve to be cautious. The War was upon them, and the dangers were real. If they were to let the boy go, what kind of information could he take back to the Union soldiers? Sadly and tragically, the circumstances of the times compelled the men in Henry Kuhl’s field to act in the belief that they were defending their lives and property.

Henry Kuhl’s neighbor, Frederick Gerwig who was loyal to the Union side of the Civil War, testified eight months later at a military tribunal in Charleston, Virginia: “James Putnam had told that Henry Kuhl and Hamilton W. Windon (prisoner) were the two men who killed the boy. Then I and two of my brothers, Mathias and Jake Gerwig, and my father and Daniel Engle went out and looked.”2 Gerwig described how they all made a secretive trip to the boy’s burial site on or near Henry’s farm. They went in the middle of the night in order to avoid being seen. It is doubtful that any of these men had the authority or skill to inspect the site. Gerwig said they dug up and examined the body, which must have destroyed evidence. “. . . the neck bone was all washed away and we could not tell anything hardly.”2

Questions

Sometime after the Gerwigs and Engle examined the body, all men who had been in Henry Kuhl’s field that day (except John Conrad) were brought before Justice of the Peace, William Corley, in Sutton where they were charged with murder. John Conrad had fled from the farm, and was not captured for the trials. It is not clear who reported the boy’s death to the authorities. Why had the military taken control of the prisoners? Why were these men denied the right to a trial by jury? Henry and his son, Conrad, were civilians. Why were they tried and sentenced by a military tribunal? This was 1861, but martial law was not imposed until 1863.13 Why were the trials held in Charleston, far from Sutton? And why were some of the key witnesses not present at the trials? Elizabeth Kuhl had been a witness to what had happened at the house while the men were out working in the field. Two of the children, Henry Jr. (age 17) and Rebecca (age 14) may have also been present. What had provoked the men to go after the boy that day? Had there been some kind of conflict at the house? Were these three witnesses given an opportunity to testify? They were not present at the trials.

Henry Kuhl, his son Conrad, and Hamilton Windon may not have been informed of their legal rights through legal counsel while they were incarcerated. In 1866, the U. S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that military tribunals used to try civilians in any jurisdiction where the civil courts were functioning were unconstitutional.3 Although the ruling came too late to help Henry and his son, it does question the legality of military tribunals in civilian cases during the Civil War. “The guaranty of trial by jury contained in the Constitution was intended for a state of war, as well as a state of peace, and is equally binding upon rulers and people at all times and under all circumstances. . . . A citizen not connected with the military service and a resident in a State where the courts are open and in the proper exercise or their jurisdiction cannot, even when the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is suspended, be tried, convicted, or sentenced otherwise than by the ordinary courts of law.”3 John D. Sutton, in his “History of Braxton County and Central West Virginia” noted that “throughout the war the courts were open, and their authority was respected.”4 He mentions several cases in which citizens were detained by Federal military authorities, and when applied to civil authorities, were released.4

After the Military Commission tried and sentenced the three men in Charleston, Henry Kuhl and Hamilton Windon were executed by public hanging on May 9, 1862 in Sutton, Virginia. Henry’s son, Conrad, was sentenced to be “kept at hard labor, with ball and chain attached to the left ankle, during the war”.2

Those Involved

Who were the individuals involved in this Civil War tragedy—the victim, the accused, the witnesses, the judges? What were their actions and responses in all of this?

“Casper Presler”: Very little is known about the boy whose name might have been Casper Presler. Frederick Gerwig, witness for the prosecution at Henry Kuhl’s trial, stated, “I supposed the boy to be a soldier. The old man [Henry Kuhl] said the boy belonged to Captain Moore’s Company. Capt. Moore was of the 10th Regt. O.V.I. . . . The name of the deceased was not known. He wrote it on a slate at my father’s house as Casper Presler, that he said was his name. He looked like a likely boy. He looked like he might have been fifteen or sixteen years old.”2 Searches through the soldier lists of this regiment as well as the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, did not find a Casper Presler. Conrad Kuhl, witness at Hamilton Windon’s trial, stated “the boy was uniformed like a United States soldier. I did not know his name.”2 Hamilton Windon, witness at Conrad Kuhl’s trial, said, “The boy was a German boy. The old man [Henry Kuhl] talked to him in German.”2 The record of the Military Commission states that the boy was “one of the soldiers of the United States Army whose name is unknown”2. Apparently there had never been an investigation to determine the identity of the boy. His identity was ignored and made irrelevant. The evidence does not seem to support the claim that he was a soldier, which would mean the case should have been tried in a civil court.13 If the boy had been a soldier, where are the military records of his service and his death?

Henry Kuhl: Henry pleaded guilty to the charge of murder. John Morrison,

Union soldier, Co. F, 10th Infantry Regiment Virginia 5, witness for the prosecution in Henry Kuhl’s case, stated that he was present when Henry confessed to the Justice of the Peace in Sutton. Morrison said that Henry first denied killing the boy, but later confessed. No written record of this was mentioned in the trial record. Such a record must have existed. We are left wondering why Henry changed his plea. Was he pressured? Was some kind of deal made?

Union soldier, Co. F, 10th Infantry Regiment Virginia 5, witness for the prosecution in Henry Kuhl’s case, stated that he was present when Henry confessed to the Justice of the Peace in Sutton. Morrison said that Henry first denied killing the boy, but later confessed. No written record of this was mentioned in the trial record. Such a record must have existed. We are left wondering why Henry changed his plea. Was he pressured? Was some kind of deal made?Right: Henry Kuhl

Hamilton W. Windon: Windon pleaded not guilty to the charge of murder. By his own admission, he witnessed the death of the boy soldier, but he said Henry Kuhl killed the boy. Windon was not provided with any kind of defense, but John Morrison and Frederick Gerwig were both witnesses for the prosecution. Henry Kuhl’s son, Conrad, served as witness for the defense, but would have been considered a hostile witness in a normal trial. Conrad said, “Windon and my father (Henry Kuhl) told me afterward that they had killed the boy. . . . The way they told me was that Windon gave the first lick and my father (Henry Kuhl) the second.”2 Windon was tried as a civilian, yet military records show that he was a Confederate soldier, who had enlisted as a Private in Company D, 31st Virginia Regiment Volunteers5. After the trials, Judge Advocate General Cornine responded to the actions of the Military Commission by writing: “Some of these men belonged to the army at the time the crime was committed. This circumstance has given me trouble, but careful investigation and reflection have brought me to the conclusion that the Military Commission had ample justification to try them.”2

John Conrad: The 1860 Federal Census for Braxton County, Virginia, shows a 17-year-old John Conrad living on a farm as one of Christopher Conrad’s children. The 1880 Federal Census shows a John S. Conrad living in Braxton County, and his birth year is 1843, which would have made him a 17 year old youth in 1861. The 1880 record indicates that he was a farm laborer, divorced, and housing three boarders. Was this the John Conrad who fled the farm and escaped the trials? Additional research would be required to answer this question.

Conrad Kuhl: Conrad’s trial was the last case to be tried by the Commission. He pleaded not guilty. He was provided with two witnesses for the prosecution, and none for his defense. The testimony of these two men, however, may have saved Conrad’s life. Union soldier, Private Ezekiel Marple’s testimony was especially helpful. When the Judge Advocate ordered Marple to state what kind of a character the prisoner had in Braxton County, Marple replied, “The people in and about Sutton who know the prisoner say that he is a quiet and peaceable man, that there is not a stain upon his character, and that he is very much afraid of his father who is a very hard man.”2 The other witness, Hamilton W. Windon, testified that Henry Kuhl killed the boy, and Conrad Kuhl had no part in it other than going up on the hill to act as a lookout to see if anyone was coming to the farm.

James Putnam: The testimony of Frederick Gerwig provided hearsay evidence that James Putnam had reported the boy’s death. Gerwig, stated, “It was reported that one James Putnam had told that Henry Kuhl and Hamilton W. Windon (prisoner) were the two men who killed the boy.”2 Elsewhere in the court proceedings, Gerwig said, “Hamilton W. Windon told James Putnam about killing the boy and Putnam let it out.”2 James Putnam enlisted in Company D, Virginia 31st Infantry Regiment on May 31, 1861, and served the Confederacy5 along with two of Henry Kuhl’s sons, Christian and John, who were also in Company D. Putnam was not present during the court proceedings, and was probably with Company D on the battlefield. Was Gerwig’s claim based on fact or rumor?

Frederick Gerwig: Gerwig, a farmer living half a mile from Henry Kuhl’s farm, said he had known Henry for 20 to 23 years. Both men were born in Germany, immigrated to the United States, and settled in Braxton County as neighbors. Gerwig provided damaging testimony against both Henry and Hamilton Windon at their trials. Gerwig does not appear to have enlisted for military service on either side of the Civil War, but indicated in his testimony that he was a Union supporter.

William L. Corley: Corley was Deputy Sheriff of Braxton County when he enlisted in the Confederate Army, Company C, 9th Battalion Infantry Regiment Virginia on May 18, 1861.5 The trial record shows that “Justice Corley in Sutton, Virginia” heard the statements of the men arraigned for the murder of the boy. On May 1, 1862, Corley transferred out of the 9th Regiment and into Company C, 25th Infantry Regiment Virginia.5 This transfer occurred only nine days before Henry Kuhl and Hamilton Windon were executed in Sutton.

John Morrison: Morrison had been Sheriff of Braxton County for a number of years. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederate guerilla company known as the “Moccasin Rangers” came to Morrison’s 300 acre farm, burned his home and drove off all his cattle and horses.4 After that, Morrison enlisted at the age of 44 as a Union Private in Company F, 10th Virginia Infantry.6 He served as witness for the prosecution against both Henry Kuhl and Hamilton Windon.

Ezekiel Marple: Marple was a Private in the Union Army, Company A, 10th Regiment, West Virginia Infantry.7 He was 39 years old at the time of the trial, where he served as witness for the prosecution in Conrad Kuhl’s case. As mentioned above, Marple’s testimony probably saved Conrad’s life. According to the 1860 Federal Census, Marple was a farmer with a large family. He died May 21, 1869, only 7 years after the trial.8

Hugh Ewing: Colonel Ewing, President of the Military Commission, was educated at the United States Military Academy, and became a lawyer. Long after the trials, on March 13, 1865, Ewing was promoted to Brevet Major-General “for gallant and meritorious service during the war.”5 His military training may have predisposed him to accept military tribunal justice, a form alien to common law, which provides for trial by jury and the presumption of innocence. In his letter to the Provost Marshal who was in charge of the three prisoners prior to the trials, he ordered the Marshal “to confine, under heavy chains, in the securest dungeon you have in your control, Henry Kuhl, Hamilton W. Windon, and Conrad Kuhl, and to keep them until you are otherwise ordered by proper authority.”9

Hugh Ewing: Colonel Ewing, President of the Military Commission, was educated at the United States Military Academy, and became a lawyer. Long after the trials, on March 13, 1865, Ewing was promoted to Brevet Major-General “for gallant and meritorious service during the war.”5 His military training may have predisposed him to accept military tribunal justice, a form alien to common law, which provides for trial by jury and the presumption of innocence. In his letter to the Provost Marshal who was in charge of the three prisoners prior to the trials, he ordered the Marshal “to confine, under heavy chains, in the securest dungeon you have in your control, Henry Kuhl, Hamilton W. Windon, and Conrad Kuhl, and to keep them until you are otherwise ordered by proper authority.”9 Above, right: Colonel Hugh Ewing.

Below, right: Colonel George Crook.

George Crook: Crook graduated at West Point in 1852. He was commissioned an officer in Company S, Ohio 36th Infantry Regiment on Sept. 23, 1861.5 He was a membe

r of the Military Commission in Charleston along with Hugh Ewing. Colonel Crook was known for his severe treatment of civilians during the Civil War. He typically followed a no-prisoners policy.16 When his troops encountered heavy guerilla resistance north of Sutton, Braxton County, Virginia in January, 1862, he responded by burning citizens’ houses and towns along his march.16 In one of his reports dated May 24, 1862, he wrote, concerning civilians who shot and wounded some of his soldiers, “The houses which can be fully identified as having been fired from will be burned, and if I can capture any of the parties engaged they will be hung in the street as an example to all such assassins.”10

r of the Military Commission in Charleston along with Hugh Ewing. Colonel Crook was known for his severe treatment of civilians during the Civil War. He typically followed a no-prisoners policy.16 When his troops encountered heavy guerilla resistance north of Sutton, Braxton County, Virginia in January, 1862, he responded by burning citizens’ houses and towns along his march.16 In one of his reports dated May 24, 1862, he wrote, concerning civilians who shot and wounded some of his soldiers, “The houses which can be fully identified as having been fired from will be burned, and if I can capture any of the parties engaged they will be hung in the street as an example to all such assassins.”10 General Jacob D. Cox: Cox, a lawyer, commanded Union troops in the Kanawha Valley that occupied

Charleston, Virginia. In his May 24, 1862 letter to Col. George Crook, he writes, “Your retaliation upon the citizens who fired on your wounded will be approved.”10

Charleston, Virginia. In his May 24, 1862 letter to Col. George Crook, he writes, “Your retaliation upon the citizens who fired on your wounded will be approved.”10Right: General Jacob D. Cox

Right, below: Major General John Fremont

Major General John Fremont: Fremont likewise thought it appropriate to carry out public executions of civilians to make an example of them so that others would know what to expect if they were to fire at Union soldiers. In his General Orders No. 17, dated April 25, 1862, he gave the same order for both Henry Kuhl and Hamilton Windon, stating for each case, “The finding and sentence in the above case are approved and confirmed, and to the end that just example may be made, the sentence will be carried into effect at Suttonville, Braxton Co

., Virginia, on Friday, the 9th day of May, 1862, between the hours of 12 M. and 1 P. M.”2 The two men were then moved from Charleston, Virginia, and taken through the wilderness, probably in chains, by Union troops under the command of Colonel George Crook to Sutton where they were publicly executed by hanging.

., Virginia, on Friday, the 9th day of May, 1862, between the hours of 12 M. and 1 P. M.”2 The two men were then moved from Charleston, Virginia, and taken through the wilderness, probably in chains, by Union troops under the command of Colonel George Crook to Sutton where they were publicly executed by hanging.In Conclusion

What did this effort to make an example of the men through public hanging accomplish? It is difficult to say what effect it had on the population as a whole. It may have intensified resentments in some of the people. It is known to have humiliated innocent members of the Kuhl family. To this day, the location of Henry Kuhl’s grave is unknown, and legends abound. In 1897, following the last public hanging in West Virginia, the body of prisoner John Morgan was placed in a pauper’s coffin, his remains were sent to the home of his wife and were buried on her father’s farm.14 Could Henry’s resting place exist in some secluded area of his farm? Time heals, generations pass, and Society evolves. By the end of the 19th Century, the barbaric spectacle of public executions had been abolished in the state of West Virginia.

Endnotes

1. Memoirs of Christian Kuhl, written in 1911, edited by historian, Roy B. Cook, Charleston, WV., Lila V. Powers collection of family papers.

2. Proceedings of a Military Commission Convened at Charleston, Virginia, March 31-April 3, 1862 in Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General, file # II-832, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

3. Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866), Syllabus Supreme Court of the United States, digital copy, Cornell University Law School.

4. John D. Sutton, History of Braxton County and Central West Virginia, McClain Printing Company, Parsons, WV, 1919, p. 191.

5. U. S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2009.

6. American Civil War Soldiers [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 1999.

7. U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007.

8. Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1879-1903 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007.

9. Union Provost Marshal’s File-Citizens, Two or More Names (Entry 465) in Record Group 109, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, File #885, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

10. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.; Series 1 – Volume 12 (Part 1), Chapter XXIV, p. 807.

11. Lawrence Wilson, Itinerary of the Seventh Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1864, The Neale Publishing Company, New York, 1907, p. 51.

12. Jacob Heater, “Some Civil War Reminiscences”, The Braxton Democrat, March 4, 1920. [Reprinted at orlandostonesoup.blogspot.com]

13. Two websites that refer to the Sept. 15, 1863 Congressionally-authorized martial law: [www.usconstitution.net/consttop_mlaw.html] and [www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/]

14. Stan Bumgardner and Christine Kreiser, “ ‘Thy Brother’s Blood’: Capital Punishment in West Virginia”, West Virginia Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. IX, No 4 and Vol. X, No. 1, March 1996. [www.wvculture.org/history]

15. The First Confiscation Act, Chap. LX.—An Act to Confiscate Property used for Insurrectionary Purposes, August 6, 1861. U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, Vol. 12 (Boston, 1863), p. 319.

16. Kenneth W. Noe, “Exterminating Savages”, The Civil War in Appalachia, Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1997, pp. 115-116.

. . . . .

Notes

Notesa. To the right is Henry Kuhl's (spelled "Cool" here) land grant for his property at the head of Butcher's Run, which is illustrated above. Click oh the image to open a larger copy of the document.

b. Henry Kuhl's farm at the head of Butcher's Run is a 40 mile ride from Orlando; much closer "as the crow flies." However. many of his descendents settled in the Orlando area. Henry Kuhl's grandson Henry Kuhl/Cole was in the Three Lick area and Henry Kuhl's son Christian Kuhl's farm was at the tip of Gilmer County where it meets Braxton and Lewis Counties.

c. The photograph of Henry and Catherine (Yeagle) Kuhl and of Elizabeth (Skidmore) Kuhl were taken from the Wilt/James/Brewer/Kuhl family tree belonging to jnnfbl91, a descendent of Conrad "Koanard" Kuhl who was imprisoned for the duration of the war for his part in killing the young Union man.

central western Virginia/ West Virginia showing the Staunton Parkersburg Turnpike and the Gauley Bridge/Weston Turnpike as they we roughly located before and at the time of the Civil War. Click on the map to enlarge it.

central western Virginia/ West Virginia showing the Staunton Parkersburg Turnpike and the Gauley Bridge/Weston Turnpike as they we roughly located before and at the time of the Civil War. Click on the map to enlarge it.